Big Brother is Listening

The Government's nasty, nervous habit of spying on itself with telephone taps and hidden microphones has encouraged a nationwide invasion of privacy.

By Ben H. Bagdikian

Saturday Evening Post 6-6-1964

One evening last year, after most of the offices of the State Department Building were closed, two hard-working men let themselves into Room 3333 and began dismantling the telephone. They were Clarence J. Schneider, a technician, and Elmer Dewey Hill, a State Department electronics expert. Working under orders of John F. Reilly, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Security, the men changed some wires, reassembled the telephone and left. For two days the innocent-looking telephone in the office of Otto F. Otepka, Deputy Director of the Office of Security, doubled as a microphone, relaying everything which was said in the office, whether or not the phone was on the cradle. In a laboratory some distance away, diligent eavesdroppers recorded 12 separate conversations.

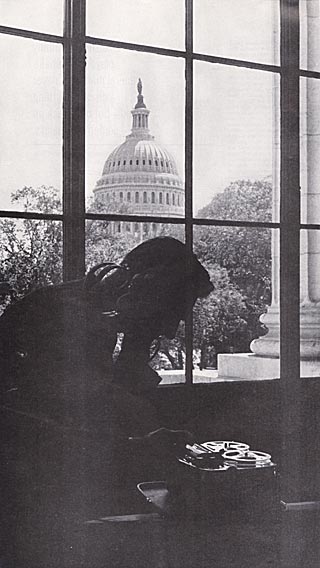

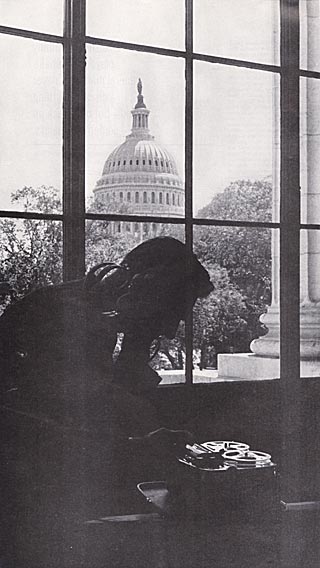

In sight of Capitol, private investigator Allen Crawford shows recording technique.

|

On July 9, four months later, Hill was put under oath by the Senate Internal Security subcommittee and asked, "Do you know of any single instance in which the [State] Department has ever listened in on the telephone of an employee?" Hill answered, "I cannot recall such an instance."

On August 6, Reilly was put under oath and asked, "Have you ever engaged in or ordered the bugging or tapping or otherwise compromising telephones or private conversations in the office of an employee of the State Department?" Reilly's answer was, "No, sir."

The parties in this particular charade were engaged in some political in-fighting. Otepka, a security officer brought into the State Department in 1953, had risen to one of the top security evaluation jobs in Washington. But now he himself was under suspicion. His superiors believed that he was feeding classified information to a hostile Senate committee in order to embarrass his boss, Reilly. So Reilly had Otepka's phone fixed to catch him in the act. He also had Otepka's wastebaskets intercepted on the way to the incinerator and combed for incriminating material. Reilly says he lost interest in the phone tap after finding in the wastebasket a piece of carbon paper with the impression of 15 questions which Otepka had allegedly typed out for Senate investigators to ask Reilly.

At the time, these two men - Otepka and Reilly - were responsible for passing judgment on the loyalty, security and reliability of American diplomats. Hill and Reilly later "amplified" their denials of eavesdropping by giving the facts and promptly resigned from the State Department. Otepka, charged with passing privileged documents without authority, carries on in a sort of limbo, marking time on the payroll while awaiting a hearing on his dismissal.

|

The story of Otto Otepka is part of the brave new world of white-collar eavesdropping in the United States Government. The eavesdropping may consist merely of a silent secretary's taking down your words while you speak to her boss, or it may be a hidden microphone recording everything you say in what you think is a confidential interview. Some governmental eavesdropping is directed against espionage and crime, of course, but a great deal more is done for bureaucratic convenience and gamesmanship, either to spring a trap on a colleague or to avoid one.

These days, consequently, if you telephone a Washington official of more than middling importance - or it he calls you - the odds are disturbingly high that a third person is listening in. They are almost as high that every important word you utter is being taken down in shorthand. And while lower, the odds are still significant that your entire conversation is being taped.

In fact, Americans are so busy snooping on one another that it has almost been forgotten that Big Brother may not be an American at all. A European diplomat recently told of having discovered a man tinkering with the wall clock in his Foreign Office chamber at home; he immediately called his security men for fear the man was planting a microphone "for our Russian friends." A short time later, an American who works for the American military in Washington made an unexpected Saturday visit to his office and found a stranger in the process of dismantling his phone. The stranger had tools draped around his waist and said he was a telephone man checking phones. The American said later that he assumed a microphone was being planted. Asked who he thought responsible, he said, "Oh, I suppose one of our spooks" - meaning a rival American military agency. Did it occur to him, as it had to the European, that the man could have been "one of our Russian friends"? The American thought about that for a moment. "Well, of course, it could have been," he admitted, "but I'm told our spooks do it so often, I just naturally assumed it was one of ours."

Electronic snooping is not confined to Government, of course. Thanks to modern science, privacy is becoming more and more rare all over the world. Even a child can send away for a $15 device that picks up sounds in a room across the street. For $17.95 you can buy a machine that secretly tapes telephone conversations without touching a wire. And $150 buys a TV camera the size of a book that can spy on a room secretly while you watch on a distant monitor. Using these and other modern methods, American business has turned increasingly to espionage in recent years.

But government has a special responsibility to keep its snooping under tight control. As Justice Louis Brandeis said in 1928, "Our Government is the potent, omnipresent teacher. For good or ill, it teaches the whole people by its example." Moreover, Government has the power to use-or misuse-secret information against the citizens it is supposed to be serving. Big Brother compiles dossiers and wears a police badge.

In addition, some eavesdropping is not only unethical but also illegal. Section 605 of the federal Communications Act says, "No person not being authorized by the sender shall intercept any communication and divulge or publish the existence" of a wire or radio message. But in vast areas everyone pretends that the law does not exist. The chief reason is that the Government itself breaks the law so often that it is loath to make an issue of free-enterprise lawbreaking. Unauthorized wire tapping and phone recordings by federal, state and local law-enforcement officials, sometimes for such unofficial purposes as extortion and blackmail, have been proved many times, but in the last 20 years not one government person has been prosecuted under Section 605.

Not all government eavesdropping has a sinister purpose, to be sure. The listening secretary can jot down dates and details, can lay a file before the boss as he talks about it, can later follow through on the discussed arrangements without being told. The mechanical recording can be filed for legitimate future reference. Moreover, in espionage and crime, the telephone is often an instrument of conspiracy; under appropriate safeguards, listening in is a proper counter-weapon.

And sometimes the government employee may simply be protecting himself. Officials are in constant danger of being accused of succumbing to improper influence, and it is understandable that they would want a record of any given conversation.

But abuses are both easy and common, and little thought has gone into their control. As a result, eavesdropping on phone calls (the polite word is "monitoring") has become so widespread that the scope of the problem can only be guessed at. There are more than 200,000 individual government telephones in the Washington area, most of them extensions on which a third party can listen. There are about 14,000 federal secretaries and 6,700 stenographers available to listen and take notes. They can do this simply by lifting an extension, but many have special attachments that permit listening in without clicks, background noises or noticeable loss of volume. Known technically as "transmitter cutoffs," they are referred to in the trade as "snooper buttons." In 1962 there were 5,317 snooper buttons on official Washington phones, most of them in important offices.

In 1961, for example, Abraham Ribicoff, then Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, received a letter from Rep. John E. Moss, the California Democrat whose mission is investigating secrecy in government. Moss asked Ribicoff whether he permitted the 5,000 HEW telephones in Washington to be used for "monitoring," and Ribicoff asked his executive assistant, Jon O. Newman, to check. Newman noticed that along executive corridors dozens of secretaries were constantly at their desks, motionless, telephone to ear, not talking. He discovered that they were "monitoring" with the help of snooper buttons. In fact, he discovered that his own secretary used one. There turned out to be 274 buttons in HEW at an annual rental of about $1,500. Ribicoff ordered all snooper buttons removed, and further directed that "monitoring" was permissible only with prior notice to the other side. His rules are still the exception in government.

Big Brother's snooping is not, of course, restricted to telephone "monitoring." There is also the hidden microphone, a device used widely in offices where men and women are interviewed. In times past, a microphone was of the carbon type-large, inefficient, with tell-tale wires that led to a live listener, usually in some cramped place nearby. Today's microphones are small as buttons, and some are self-contained miniature broadcasting stations capable of transmitting to a radio receiver blocks away. They can be dropped in an office wastebasket, made part of a man's tie clasp or even put inside a woman's girdle. Some segments of official Washington are so microphone-conscious that their meetings strike visitors as rituals of lunacy. A newcomer to the Pentagon's high-powered military rivalries, for example, described with wonderment a conference of one branch's top brass making plans to fight the appropriation of a sister military service.

"When we got to the crux of the plans," he said, "we all went to the center of the room, away from walls and telephones, and spoke in low voices while one officer kept rattling the table. They said it would interfere with any bugs." (In the vocabulary of eavesdropping, a "bug" is a hidden microphone; a "tap" is a secret interception of a phone call.)

There is, it turns out, a body of folklore on how to frustrate Big Brother. Some people rap the telephone with a pencil as they talk. Others run water, pound a table, or keep a radio or TV set turned on. Whether these tactics work depends on how good the eavesdropper is and how hard he is willing to work to extract the message. Rapping the phone doesn't help much. Running water is moderately good, but a determined snooper can filter out most of the sound electronically. Banging a table may jar a bug. But the most sophisticated warriors keep a radio or television set turned on loud while they speak softly and continually face in different directions (which is the reason well-bugged hotel rooms and offices have a least four hidden microphones.)

The most strategic sessions in government are held in rooms that have been "swept"-that is, scanned by metal and radio detectors. And the really crucial conferences are held in a "portable room" erected inside a "swept" room. These consist of four lead-like portable walls plus ceiling and floor, all latched together to make a chamber within a chamber. Furniture for the conference is usually made of glass to make concealment of microphones difficult. There are no windows, because the human voice causes windowpanes to vibrate, and a laser beam can "read" these vibrations from the outside. There are offices in the State Department where the shades are always drawn to protect against laser beams and telescopic lenses.

These precautions are taken mainly to guard national secrets from foreign spies-and there is abundant evidence that enemy agents eavesdrop in every way they can. But by far the greater number of attempts to snoop involve one bureaucrat spying on another bureaucrat. The practice is so common that any time an agency begins looking for illegal eavesdropping it is in danger of bumping into itself. Last year, for example, a Congressman took over an office just vacated by a subcommittee chairman and found one telephone with no apparent purpose. By experimenting, he found that its snooper buttons let him listen secretly to any conversation by the staff of a committee in a nearby building. He had the line removed. The late Sen. Thomas Hennings Jr. once waxed indignant about the Government's use of new miniature German wire recorders and ordered his committee to find out who had used tax money by buy them. It is typical that he found his own committee staff had three of them. It was untypical that he admitted it.

Most government eavesdroppers take the same attitude toward snooping that Victorians took toward sex: deny its existence if you can, and if you can't, refuse to talk about it. In 1961, when Congressman Moss asked government agencies if they ever used listening-in or recording devices on telephones, Byron White, then the Deputy Attorney General, replied, "The Federal Bureau of Investigation advises that it does not utilize the devices referred to in your letter." That same year Assistant Attorney General Herbert J. Miller Jr. told a Senate committee that on a random day the FBI had 85 wiretaps in operation.

The State Department admitted that it had 802 snooper buttons, but added, "There are no other electronic devices used in the department to monitor telephone conversations." It further pointed out that a departmental directive requires all recording of conversations to be done only with advance notice to the other party. This directive was in force during the Otepka episode.

Such conflicting answers are common. Government officials prefer not to discuss the subject at all, but most are inclined to regard it as a necessary evil.

This comes close to reflecting the attitude of the public as well, an attitude which has changed significantly over the years. During prohibition, for example, eavesdropping became an important law-enforcement (and lawbreaking) tool. Under Hitler it became an instrument of terror, associated in most people's minds with secret police.

In the United States, it started out simply as an instrument of efficiency. In 1938 the Army asked its switchboard operators in Washington to make recordings of all long-distance calls, after first warning both speakers. The idea was to preserve technical data. By 1940 the volume of calls was so heavy the recording held up switchboard operations, and the recording was shifted to users of individual phones. At the same time, the warning was dropped. This kind of recording was done on special machines connected to the telephone with jacks, and by 1946 the Army and Navy had 5,700 of them. But by this time hundreds of people had discovered "instant wire tap"-a simple inductions coil under the telephone that turned a dictating machine into a recorder. Many government officials, including Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, used this as a routine office aid, a simple administrative convenience.

Today the practice has grown to the extent that there is a widespread assumption in government that "someone" is always listening. Whenever their telephone line makes a click, some call, "Yoo-hoo, Edgar!" in a left-handed salute to J. Edgar Hoover. And a number of people echo the complaint of Sidney Zagri, a Teamsters Union legislative counsel who told a senatorial committee that when he is in Washington he has to keep shifting to public pay stations to prevent all his business with Congressmen from being overheard. (Mr. Zagri will be pained to learn that law-enforcement agents tap more public phones that private phones.) In governmental telephone conversations, and often in private conversations, too, confidential details are never given on the telephone. And the dialogues are often couched in such terms as: "I heard from our nervous friend, and we're going to meet at the usual place where I'll pick up the paper he wants our man to deliver."

Once people believe that Big Brother is on the line it makes little difference whether he really is or not-a point illustrated by an episode in Congress a few years ago. In early 1961 the Kennedy Administration suffered several setbacks in the House of Representatives on votes for which White House aides had collected commitments for enough "yesses" to ensure passage. Obviously, come Congressmen were promising yes and voting no when the measures were brought to the floor. This happened most often on "teller" votes, in which Congressmen line up in "yes" columns and "no" columns and march toward the rear of the House, where a teller counts the number of men in each line without recording their names. Since White House aides are supposed to leave the chamber during the process, anonymity is preserved.

On March 24, 1961, the Administration lost by 186 to 185, a vote that it had expected to win. The next day a rumor was heard in the House cloakroom that a miniature camera had been installed in the great clock at the rear of the chamber-a camera capable of taking motion pictures of the men as they lined up on teller votes. Four days later another crucial bill came up, and this time the Administration got exactly the votes it expected. And as they trooped up the aisle, several Congressmen were seen to smile heroically toward the clock. There was, of course, no camera; the point is that a significant number of lawmakers believed that such a tactic might actually be employed.

But while the Federal Government has not gone this far, it has gone far enough. And unless Uncle Sam seriously intends to become the kind of all-seeing, all-hearing Big Brother that George Orwell wrote about, strong preventive measures must be taken-and soon. Nothing the Government can do will end all the evils of snooping, but a useful first step would be to clear up the present tangle of law and precedent on eavesdropping. Today the highest legal authorities differ on what the federal law means. Some say that tapping a phone by itself is a crime; others say it is criminal only when intercepted messages are disclosed. But even in cases where everyone agrees it is a federal crime, it is still legal in those states with laws which are contrary to the federal statute. Six states permit wiretapping, 33 specifically prohibit it, and 11 don't have any law either way.

Since 1962 there has been pending before Congress a bill approved by the Department of Justice that would end some of the confusion. It would permit federal authorities under the Attorney General to wiretap with court orders in certain situations-espionage, subversion, murder, kidnapping, interstate racketeering, narcotics-and in espionage cases the court order could be skipped if the Attorney General felt that asking the court would endanger the national interest. The states would be permitted to tap only under their highest law-enforcement official, with a court order, and only when a serious crime was involved-murder or kidnapping, for example. All other wiretapping, public or private, would be specifically prohibited, a crime punishable by $10,000 fine or two years in prison or both.

The bill has been stalled for two years. Some legal authorities think it still permits too much latitude for tapping. Some law-enforcement agencies argue that it is too restricting. The controversy, according to most governmental experts, can be settled when Congress gets down to it, but in this year of even greater controversy it is not likely.

In the meantime, snooping within government itself could be considerably reduced by an executive order from the President, setting down uniform practices and principles to end the present pattern of every bureaucrat's being a law unto himself. Either way, unless firm measures are taken soon to end the Government's degrading habit of spying on itself, the mental attitude which the practice reflects may become so firmly established that no one will be left who realizes the danger of having Big Brother in Washington.

|