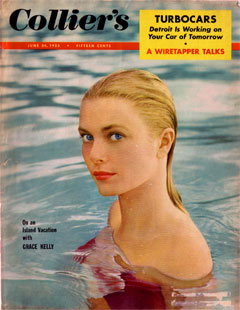

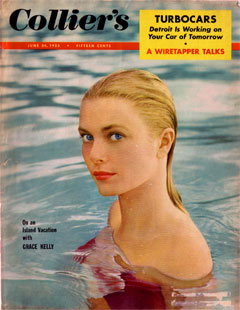

Who Else is Listening?

How to Stop Wiretapping

by Bernard B. Spindel with Bill Davidson - Collier's, June 24, 1955

There's no certain technical defense against electronic eavesdropping, an expert says. That leaves only one way to halt this threat to our traditional right of privacy: new, rigidly enforced laws to control the snoopers' activities

I tapped my first telephone when I was twelve years old. The victim was a young girl in my neighborhood in the Bronx in New York City. I had developed a puppy-love crush on her and I wanted to find out who her boy friends were. So I used techniques taught me by a retired telephone-company employee who frequented a radio repair store where I practiced my hobby of electronics. I listened in on the girl's conversations-and those of her father and mother-for two weeks.

Since then I have tapped perhaps 3,000 phones and installed about 1,000 electronic eavesdropping devices-hidden microphones, tiny radio transmitters and the like. I did my undergraduate work in electronics snooping in the late 1930s and early 1940s when I was a radio technician and did wiretaps in my spare time; I earned my master's degree in eavesdropping in World War II in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, which loaned me out to various government agencies; and I got my Ph.D. in the postwar period while operating as a private detective and as an electronics expert available for hire by other detective agencies all over the country.

My long education in ways and means of invading privacy has led me to one major conclusion: there's no complete, practical, technical defense against electronic eavesdropping; the only feasible source of protection is stringent legislation-accompanied by an awakening of the public to the dangers to their constitutional right of privacy raised by new electronic devices and techniques.

There's no way an ordinary citizen can tell for sure whether anyone is listening in on his telephone line. Most people think that clicks and fading tip them off if wiretappers are at work. That's an old wives' tale. A properly installed tap gives no clue whatever to its presence. Other people have come up with the myth that you can foil wiretappers by using your phone in a bathroom or kitchen with water faucets turned on full force. But if the other party can hear you, so can the wiretapper. Moreover, the expert electronic eavesdropper can filter out all extraneous noise in recordings of a conversation.

There is a variety of so-called "tap testers" on the market. They do little but lull those who use them into a false sense of security. I know from experience that they will reveal only the most elementary type of wiretap. I have come up against them perhaps 25 times, and not once have they betrayed my taps.

In one recent case, my client was a television producer involved in a cross-petition divorce case. He knew his wife had obtained grounds for divorce against him and was planning to ask for sizable alimony. His best defense, he figured, was to try to get similar evidence against her. That was where I came in. I installed a wiretap on the family phone at a bridging point in an apartment-building basement near their home, connecting the terminals of the phone to another line running to a hotel about three blocks away. Then I rented a room in the hotel and set up my "plant," or listening point. The moment I started to check the line, I heard an almost inaudible low-frequency sound. It tipped me off immediately that there was a tap tester on the phone.

This particular type is placed next to the phone and connected to the line. Before someone makes a call, he presses a button on the device; if there is any electronic unbalance on the line-such as would be caused by an ordinary wiretap-a meter registers the fact.

To foil the device, I merely yanked my clips off the line and installed a specially designed electronic unit. The signal from my client's phone then fed into a series of radio tubes which automatically compensated for any unbalance caused by my wiretap-and the tap tester continued to register that the line was safe. My client's wife, deluded into carelessness, held long, intimate conversations with a man friend. The conversations were preserved on tape by my recording machine.

A Terrible Shock for a Lady

When the case came to trial a few weeks later, the errant wife still firmly believed that no one could have eavesdropped on her conversations. She was visibly shocked when we started to play the recordings, and she whispered nervously to her lawyer. He addressed the judge. "Don't play them," the attorney said. "We concede that it's her voice and that the conversations took place." The judge held that both husband and wife had committed adultery and threw out the cross suits for divorce.

In all my years as a civilian wiretapper, I have been caught at work only once-and that was by a suspicious bookmaker who had had long experience with police wiretappers. On every other occasion I have worked unmolested at telephone-company terminal boxes-in basements, on telephone poles and in back yards. Most people assume that I'm a telephone repairman because I carry the same tools. Several times I have installed wiretap connections on telephone poles while chatting amiably with a policeman lounging in the street just below.

If you suspect that your line is being tapped, you can notify the telephone company or call in a private technician like me. All the telephone company or other technicians can do, however, is to check all the lines and terminal boxes between your home and the telephone exchange. They look for wires connecting your telephone line with another pair of outgoing wires. If they find them, they can destroy the tap by yanking out the connecting wires-but that's no guarantee that the tap won't be put back there or somewhere else five minutes later.

Moreover, certain types of wiretaps are all but undetectable. I recently demonstrated to a Congressional sub-committee investigating wiretapping a still-secret method which uses no visible connecting wires whatever-yet enables a tapped conversation to flow between terminals of the tappee's telephone line and a plant. In a recent divorce case in a Midwestern city, I used this method because the wife involved had had previous experience with wiretappers and she was ultra-cautious. My invisible tap withstood 16 inspections by telephone-company technicians and private detectives-and three months later trapped her making dates with her boy friend.

Another nearly undetectable device is the induction coil, which intercepts the magnetic field of a telephone line and picks up conversation when merely placed or held near the phone; no physical connection is needed. The induction coil does have some limitations, however. As I told the Congressional subcommittee, the best chance of foiling an eavesdropper lies in using a pay phone next to a window in which there is a neon sign. It's unlikely the pay phone would have a regular tap, and the transformer of the neon sign emits enough electronic noise to drown out any conversation that might be picked up by an induction coil.

But even then you might not be completely safe. A big wiretap center uncovered recently in an apartment on East Fifty-fifth Street in New York City cut directly into eight telephone exchanges handling most of the city's big businesses, the wealthiest Park Avenue and Fifth Avenue homes, many foreign consulates and the UN headquarters. The tap lines ran from the main frame of a big telephone building in the block behind the apartment. The center could tap some 100,000 phones with the ease of a telephone girl operating a switchboard. There was not a single tap-free telephone on the East Side of New York between Forty-fifth Street and Sixty-fifth Street.

Obviously telephone-company employees were involved (no one else has access to the main frame of a telephone exchange), and two phone technicians were soon indicted by a grand jury and dismissed by the telephone company. A few weeks later, a private detective was indicted as the mastermind of the operation. The 14-count indictment charged the detective with attempting "to obtain detailed information on certain persons he was investigating privately for some of his clients."

Various Victims of Wiretappers

Among those whose phones were tapped were a former law partner of New York's police commissioner, an art dealer, several models, some erring husbands and wives and a big pharmaceutical house. A reliable source told me that a typical client of the illegal wiretap center was an insurance investigating bureau trying to run down information on suspicious-looking claims. The press said another client was the late financier, Serge Rubinstein, who operated on the premise that the most efficient way of doing business was to know what your opponent was up to at all times.

The ease with which electronic eavesdroppers can listen in on almost anyone's conversation makes all the more frightening the fact that defense against them is so difficult. The snoopers use hidden microphones, tiny line-carrier transmitters which transmit the human voice over ordinary electric power lines, contact microphones which enable them to listen through solid walls, minute radio transmitters that can be hidden in a couch, a brief case or a vase of flowers-plus a dozen other diabolical listening devices. To make reasonably sure that a room is free of "bugs," as we call the electronic eavesdropping gadgets, you would need a minimum of $25,000 in equipment-and even then you'd have no absolute guarantee that it was clear.

First of all, you'd need a sweep signal indicator. The device scans all know radio frequencies. If a radio transmitter were hidden in the room, the sweep signal indicator would indicate its presence. Next you'd need a metallic object locator-similar to the mine detectors used by the Army but many times more sensitive. This gadget will locate every nail in a wall and trace all wiring. It can distinguish between wiring that carries normal house current and wires with low-voltage current which electronic eavesdroppers use for hidden bugs.

Another expensive but necessary device is a radio signal carrier detector, which tells if power lines are carrying a signal. A fourth device is a special high-frequency generator, which sends a signal over the telephone lines. After placing the signal on the line, the technician goes to all terminal boxes between the room he is sweeping and the telephone exchange. If he picks up his signal anywhere but on the lines belonging to his client, he knows that someone has "cross-patched"-visibly or invisibly-a wiretap or a bug (which also can transmit messages over telephone lines). Several other gadgets also would be needed.

To be completely safe against electronic eavesdropping today, you would have to construct a special conference room deep in the interior of a large building. The room would have to be windowless to protect it from the parabolic microphone (whose dish-shaped "ear" can pick up and amplify conversations through open windows from some distance away). The room would have to be encased in heavy metal to thwart any still-secret eavesdropping devices set up outside the room and to reduce the effectiveness of any radio transmitters hidden inside.

Within the metal sheath there would have to be an inner shell of transparent plastic, separated from the metal by about six inches and resting on transparent plastic supports. This would foil contact microphones which, when placed against a resonating surface such a nail driven through a wall, pick up conversations on the other side of the wall. Moreover, all the wiring in the room would be visible through the plastic shell; any tampering with the lines would be immediately apparent. There would, of course, be no telephones.

Prohibitive Cost of Privacy

The government is moving in the direction of such top-secret conference rooms. It already is using a metal sheath in the form of steel mesh embedded in the walls. But can the ordinary citizen indulge in such prohibitively expensive means of assuring himself the privacy guaranteed by our Constitution? Of course not. That's way I say there's only one feasible defense: new laws that would make electronic eavesdropping a felony and provide stiff jail sentences for violators.

Let's take a look at the laws as they stand now. In a memorandum to the Senate Judiciary Committee on April 28, 1954, U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr., wrote: "Ten states permit the authorized tapping of wires. Twenty-three states, although limiting in some form the tapping of wires, do not prohibit the admission in evidence of information obtained in violation of their laws [which would include evidence obtained by wiretapping]... From this analysis it would follow that although many states have declared that evidence obtained by wiretapping is illegal evidence, more than 30 states apparently allow the admission, in their courts, of evidence obtained through the tapping of wires."

Federal agents are not permitted to use wiretap evidence in federal cases-and that's why the espionage conviction against former government girl Judith Coplon was reversed even though Justice Learned Hand declared that her guilt was plain. Notwithstanding, the FBI has been allowed to tap wires by authorization of the Attorney General since 1941, and the Justice Department reported in April that the FBI was tapping nearly 150 phones-all in connection with national security cases.

Our state laws are a hodgepodge-mostly, according to William Foley, counsel of the House of Representatives subcommittee investigating wiretapping, because the statutes were passed many years ago for the principal purpose of protecting telephone-company property rather than the privacy of citizens. In New York, an assistant district attorney or any police officer above the rank of sergeant can get a court order to wiretap from any lower court judge, and witnesses have testified at Congressional hearings that judges often do not even look at an application before signing it.

The court orders are used mainly in bookmaking and prostitution cases, and William Keating, then counsel for the New York City Anti-Crime Committee, told the Congressional subcommittee that police use their wiretaps mostly to shake down bookies and pimps. Many of these court orders are for taps on pay phones; an innocent private citizen using one of the phones conceivably could become the blackmail victim of a corrupt cop.

There were more than 1,200 legal wiretaps in New York last year. Add to that an estimated 4,000 illegal taps by unscrupulous police and private individuals and you get some idea of how electronic snooping has grown in this country.

In 32 states, it's legal to tap your own phone to obtain evidence against, say, a philandering spouse or a dishonest employee. Also, I know of only one state, Massachusetts, where there is any prohibition at all against the newer forms of eavesdropping with such devices as hidden microphones and radio transmitters. I shocked the Congressional subcommittee recently when I told them some of the dangers of these loopholes in the law. I said: "Assume that I have bugged the confessional booth of a Catholic church. A confession of a crime to a priest is supposed to be a privileged communication. Yet the law in my state of New York says that by virtue of the fact that the conversation was overheard by me, a third party, the privileged status no longer exists. Furthermore, a recording of that conversation is considered competent evidence and could be used to obtain a conviction against the confessor. Extend this to an attorney-client relationship. The implications become frightening. Federal laws covering this form of eavesdropping are nonexistent. Yet it violates the basic principles of freedom."

That's why, even though I have operated within the law, I have grave misgivings about my work. Nearly all of my cases have involved bugging or the tapping of my clients' own phones. Both practices are legal, but it worries me to think of what might happen if my methods or equipment got into the wrong hands.

Bugging a Union Headquarters

Not long ago, for example, I was called to a big Southern city to bug and wiretap a union headquarters. The union president suspected that there were one or two disloyal individuals on his executive board. I worked all night every night for two months in the union headquarters building. When I was finished, I had tapped the entire phone system and equipped it with an automatic selector that permitted the president of the union to monitor any phone by remote push-button control. I also had hidden microphones in the men's rooms, in the cafeteria and in the reception room.

With the aid of these devices, the president caught two union leaders accepting bribes from business officials. The electronic setup was one of my best. But it's troubled me ever since. The current president of the union is an upstanding, honorable man. But-I ask myself-what might happen if a dishonest, power-hungry man succeeds him? A corrupt official could use my system for blackmail, intimidation and spying into private lives.

When I accept a job, I never know-except by instinct-whether the motives of my client are honorable. In one Midwestern case, I provided my client with several tiny recording machines such as fit in a shoulder holster under the coat. He convinced me he wanted them to record conversations in crucial business conferences without his opponents' knowledge. But after I left, he went one step further. Some of his associates were summoned before a grand jury. To ensure that they did not double-cross him, I heard later that he made each man wear one of the hidden miniature recorders into the jury room. Thus he violated the law by eavesdropping on grand-jury hearings, the secrecy of which is a jealously guarded American right.

When Many Secrets Are Bared

Even in a routine divorce case, the lives of many people are laid bare in my wiretap recordings. I hear discussion with psychiatrists, doctors, intimate friends. I hear other people reveal wrongdoings that have no connection with the case on which I am working-and I often wonder if my client might use this information dishonestly later on. In a divorce case, moreover, I sometimes must employ devices which may give my client-or even the victim-ideas about other possible uses for them.

Once in New York City I had to get evidence against a philandering bakery executive who was holding trysts at night in the parking lot of his bakery. The lot was surrounded by a high fence, topped with barbed wire, and the gate was triple padlocked. It would have been impossible to break into this stockade for a normal raid, so I resorted to electronic means.

One evening when the executive's car was parked outside his home, I drove up alongside and got out as if to check my tires. I then dropped a tiny radio transmitter-no bigger than a pack of king-size cigarettes-into the back of the executive's car. I reached in and pushed the transmitter under the front seat. Later that night, I sat in my car outside the barricaded parking lot and with a powerful radio receiver recorded every sound of the executive's meeting with his girl friend. The evidence helped my client, the bakery executive's wife, get her divorce-but in the interim the executive had found the transmitter in his car. I've sometimes wondered since, what if he decided to use it for business intelligence purposes against his competitors?

On the other hand, I know how important electronic monitoring can be as part of a citizen's paramount right of self-defense. One of my best friends today is an ex-client, a West Coast TV personality. He suspected that his wife was unfaithful and that she was trying to maneuver him into a divorce with crippling alimony payments. Being blameless himself, he at first refused to believe what he suspected. He was working himself into a state of nervous collapse when another detective agency referred him to me.

I convinced him that he ought to install a wiretap on his own phone-to learn the truth once and for all. I connected the tap in the basement of his building and set up my plant in a vacant apartment just above his. For eleven weeks we listened to the wife and her lawyer plot to take the husband for every cent he had, and finally we overheard the wife arrange a rendezvous with her boy friend in his apartment. We raided the apartment at 4:00 a.m. My client got his divorce-and was not required to pay alimony because of his wife's proven misconduct. If it hadn't been for the wiretap, my client might have lost his children, his home and much of his income.

Electronic monitoring may even prevent a murder. One of my former clients, a New Jersey union leader, was involved in a jurisdictional dispute with another union, later revealed to be controlled by a mob element. I had put a tap on my client's phone in a successful maneuver to catch a disloyal subordinate. The tap was still on when my client received a call from an official of the rival union. After identifying himself, he said, "Stay out of this neck of the woods, or they'll find you floating in the river." After several more threatening calls, we played the recordings for the attorney of the opposing union. Not only did my client get an amicable settlement of the jurisdictional dispute, but the rival union offered him a bodyguard. "If anything happens to you," they said, "we don't want to be blamed for it."

Murder Threat Was Carried Out

A similar case-but one that had a less happy ending-involved Tommy Lewis, president of a building-service employees union that controlled workers at the harness-racing tracks in New York State. Lewis called me back from a Montana vacation after his life had been threatened over the phone. He suspected that someone in the union was working with the thugs who were threatening him. The very day I completed my bugs and wiretaps, Lewis was killed by a hired gunman at his apartment house. I'm convinced that if I'd got my recording machines operating a day earlier, he'd be alive today. I know from experience that his best insurance policy would have been tape recordings of the conversations among the plotters.

There is no area where defensive wiretapping and bugging are more vital than in the business world. One of my clients is a big Eastern chain of auto-supply stores. Its electronic-brain business machines had revealed that one of the larger stores was requisitioning considerable more merchandise than it was selling. The company had put private detectives to work in the store, but after several months they hadn't found any evidence of wrongdoing. However, within three hours of installing a tap on the store manager's phone we heard the manager brag to another store manager how he had worked out an ingenious method of selling $36,000 worth of merchandise on his own in such a way that the merchandise wouldn't show up in his bookkeeping until a much later date. The manager was arrested the next day and signed a confession.

A Salesman under Suspicion

But all electronic eavesdropping is not so easy. Perhaps my most difficult case involved an importer of Swiss watch movements who was having trouble with a high-priced salesman. The salesman was suspected of breaking his contract with the company, and the importer wanted recordings to prove it. He wouldn't let me tap the salesman's phone, so I had to install a concealed microphone in an air-conditioning duct in his office and run my bug wires all the way to the rear of the loft. The only place for me to hide with my recording machine was in a vault where hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of watch movements was stored.

I had to work all night to run my bug wires into the vault in such a way that the alarm wouldn't go off and warn the salesman. But the worst was yet to come. I was shut in the vault at about 9:00 a.m.-and suddenly I thought I would go out of my mind. Some 50,000 watch movements, each wound by machine every day, were ticking all at once. It sounded like a waterfall, or the dripping of a thousand faucets. No medieval Chinese torture could have been worse. Finally, about 11:30 a.m., I heard the salesman say to the president of the company, "Sure I'm swindling you, but there's nothing you can do about it. I'm breaking this contract verbally, but I'd like to see you prove it with no witnesses."

That was all I needed to hear. I grabbed my recording machine and a moment later my client opened the vault door to let me out.

While I continue to do such self-defense eavesdropping jobs, I go through a constant moral struggle about them. It has colored my whole thinking about legislation to control electronic eavesdropping. On the whole, I'm for an outright ban. As Attorney General Brownell said, "Wiretapping has been brought into disrepute because of widespread abuse of it by private peepers." He might have added-abuse by some official peepers, too.

From experience, however, I know that some exceptions must be made. First, I think wiretapping and bugging by the FBI and other government agencies should be permitted in treason, sabotage and nation-security cases-but only under the most careful safeguards. If spies know they may be tapped and bugged, they will be forced to contact their accomplices in the open. Even so, such wiretapping would be so subject to abuse that I think a nonpartisan six-man federal commission of leading citizens should be set up to pass on all federal wiretap orders before they are issued.

Second, I think we should retain the right of a citizen to wiretap and bug his own premises for self-defense. But here, too, I would set up strict safeguards. I think we should license all technicians in the field (no license is required today) and police their activities. If anyone misuses information obtained from self-defense wiretaps, he should be given a long jail sentence.

It would be idealistic, of course, to expect such drastic laws overnight. But at least we're moving in the right direction. Although there have been 11 previous Congressional investigations of wiretapping without positive results, the current probe-by a House Judiciary Committee subcommittee headed by Representative Emanuel Celler (D., N.Y.)-appears determined to take constructive, realistic action. Congressman Celler appreciates the problem. He told me, "We cannot legislate for just the telephone when electronic devices seem to be equally dangerous and there is no law at all controlling them."

Wiretapping-a Federal Crime?

William Foley, the subcommittee counsel and a former Brooklyn assistant district attorney, says: "We're going to recommend legislation that will set up a new crime-wiretapping-for the first time. We'll make it a federal offense, a felony punishable by at least a year and a day in jail. We'll also make it a crime to use the fruits of wiretapping, even though the user doesn't actually tap the line himself. We think we can make all wiretapping a federal crime because all telephone lines have interstate connections. Once the crime is established, we'll set up exceptions-such as cases involving the national security, in which we'll insist on proper safeguards. We'll probably recommend that federal wiretap orders must be signed by federal district judges."

How would such legislation affect me? It probably would put me out of business. But I don't care. I can still design and manufacture specialized electronic equipment for the law-enforcement agencies that will be permitted to operate under the new laws.

In fact, I'll be happy to get out of the profession of eavesdropping, for as Congressman Celler has said: "The more we delve into this grave matter, the more we realize how the safety of our country depends on the protection of the privacy of the citizen as guaranteed by the Constitution-the privacy of his home, his business and the free words which he utters to his free fellow Americans."

|