| Home | Info | About Us | FAQ | Contact Us |

When Walls have Ears, Call a Debugging Man

| |

Counterspying. These case histories both are examples of what the sound men call legitimate bugging or counter-intrusion. In each case, a company was exercising its right to guard its own security. This is the end of the business all the electronic surveillance operators claim to be in. |

|

|

Smaller and smaller

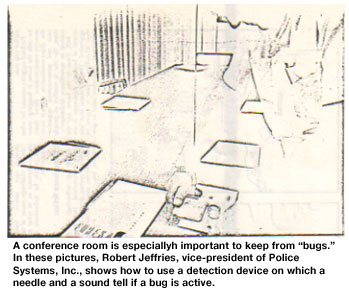

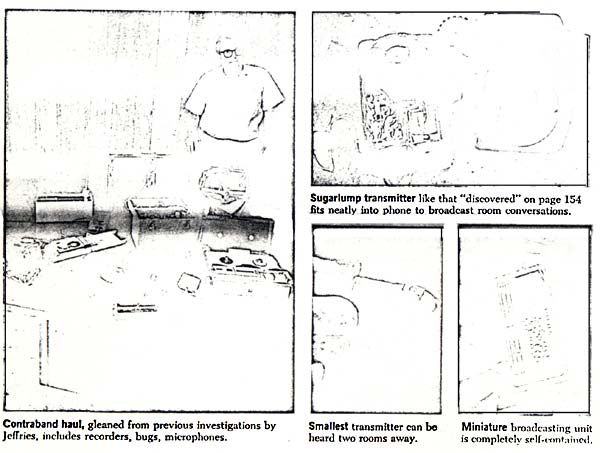

II. In the business In the U.S., two companies dominate the manufacturing of electronic listening and detection devices. Mosler Research Products, Inc., of Danbury, Conn., a wholly owned subsidiary of Mosler Safe Co., is believed to have about half the market; it talks freely about its work. Fargo Police Equipment Co., of San Francisco, is said to do about 20% of the business; it shuns interviews, and its fat catalog of surveillance equipment is marked confidential. According to Fargo's Washington representative, the rest of the business is scattered among 100 companies. Jeffries says one of these companies, Kel Mfg. Co., of Belmont, Mass., is so secret that it pretends not to exist. Using the equipment. Jeffries claims to operate only in the counter-intrusion end of the business. He says he has retainers from several clients, whose board rooms he checks regularly to make sure they are "clean"-not wired for sound by some outsider. He quotes high fees for the work, saying that debugging equipment is expensive. One sophisticated receiver costs $30,000, another $55,000. Jeffries operates a 1964 Lincoln fitted out as a rolling radar station. With his mobile and portable equipment, Jeffries claims he can locate listening devices through the radiation they give out. Fee schedule. Harold K. Lipset, president of Lipset Service of San Francisco, says the cost for a telephone tap runs from $75 to $250 a unit, and room microphones from $150 to $350. A search for bugging devices costs $250 for an average-sized office, $100 for a small conference room. The bill to assure security for a meeting of 100 persons at which every chair and every person must be checked can run up to $1,000. Monitoring office phones and tapping the premises in states where this is legal will cost $50 to $100 for each eight-hour day per eavesdropping device, or $10 per hour for the investigator's time plus equipment. III. Mosler's experience Mosler Research Products has been a subsidiary of Mosler Safe only since 1956 but has been selling security equipment for 18 years. It has three product lines: alarm systems, which are sold to banks, government offices, and factories; electronic investigative equipment (bugging devices), sold only to federal, state, and municipal agencies and licensed investigative agencies; and electronic anti-intrusion equipment (anti-bugging devices), sold to these and to private industry as well. Ralph Ward, vice-president of sales, says most demand for debugging equipment has been from government agencies and defense contractors. There has been a spurt in demand recently from companies that don't have defense contracts. "There is a greater awareness of the need to protect designs, formulas, and procedures," Ward says. Top to bottom. Last year, Mosler installed an elaborate security system in a nine-story drug laboratory on the East Coast. An electronic master console monitors 120 points in the building. Every time a door opens, a light flashes on the panel and a bell rings; a record is also printed on a tape. If the guard monitoring the panel suspects something is wrong, he sends another guard to investigate. This system cost $130,000. "That's not cheap," says Ward, "but you have to remember that the company's research achievements are its lifeblood, and the loss of a key formula can cost it may times the price of the system. For company use. Mosler sells three kits for use of company security departments. A radio receiver kit costs $550; transmitters, between $150 and $220. A $315 wire investigative kit permits tapping of any wiring system, phone line, TV antenna lead-in, office intercommunications line, or doorbell. Mosler's security or search kit for $310 has been sold by the hundreds to company security officers who need to check for wiretaps, hidden microphones, and radio transmitters. The kit includes a radio frequency probe, amplifier, headphones, and a metal detector. Self-protection. What protection does a company have from intrusion by electronic devices? Not much, says Jeffries. Even in California, where laws prohibit the practice, electronic surveillance continues. To safeguard phone conversations, Delcon Corp., of Palo Alto, Calif., makes a self-powered scrambler that the user holds over the mouthpiece. The person at the other end of the wire must have an identically coded scrambler to understand the garbled speech. Price is $550 a pair. |

|