Who Planted the First Bug?

(Newsweek, July 30, 1973)

It came as a genuine shock to some, an occasion for piety and feigned innocence to others-and as cause for a knowing wink from a well-traveled Soviet journalist. "You Americans are naïve to get excited about President Nixon bugging his office," the Russian said. "It's standard operating procedure." If it was SOP, it hasn't always been-but the sense of unease, outrage or imminent 1984 among many Americans was not much placated by the next disclosure: that Presidential eavesdropping is a practice dating back at least 40 years.

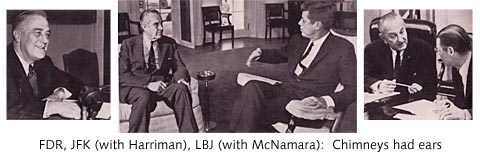

Franklin Roosevelt was the first President known to have taken secret minutes of conversations with visitors. According to Ira R.T. Smith, the White House's mail chief for 51 years until his retirement in 1948, FDR had the Secret Service build a sort of wooden chimney extending from floor to ceiling in an old storeroom underneath his executive office. The chimney had a padlocked door and room for a desk and chair inside. According to Smith's memoirs, one of the White House's better stenographers regularly disappeared into the little padlocked office. When Smith made reference to it one day, the stenographer laughed and replied, "Oh, I was just getting some reports from upstairs."

As far as the memories of old Washingtonians can recall, that was the end of the secret in-house bugging until the Kennedy Administration. Last week's revelations about Mr. Nixon's ubiquitous tapes flushed the information that 193 secret recordings of John F. Kennedy's telephone conversations and meetings, some personal and some dealing with foreign affairs and national security, have been stored with the Kennedy records in Waltham, Mass. A few at a time are being sent down to Washington to be transcribed by a secretary working for the Kennedy family, according to a spokesman for Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (who has reportedly not had the heart to read or listen to any of them.)

Last week's admissions by the White House carried with them the assertion that Mr. Nixon was only continuing the practices of Lyndon Johnson's Administration-a charge that brought a quick denial and then a quick turnabout by LBJ's old lieutenants. The Cabinet Room, it turns out, was routinely bugged in the latter years of Johnson's Presidency-but nearly everyone seemed to know it. Johnson also had a push-button recording device attached to his telephones, and he occasionally asked a secretary to make transcripts on an extension phone. Almost all the old Johnsonians were horrified, however, at the unverified report that the little green room off the President's office might have been bugged. It was in this room, known as the "think tank," that the Texas Mafia swapped ideas, gossip and uninhibited pungencies, and one old Johnsonian swore last week that LBJ "wouldn't have talked the way he talked if he thought he was being taped."

According to a Nixon ex-staffer, there have been plenty of "juicy conversations" among insiders in Mr. Nixon's Oval Office as well - "especially in talking about personalities." But few of Mr. Nixon's official visitors seemed to think that the bugs had caught them with their finesses down. "We always operate on the assumption that someone somewhere is taping everything, " said an Austrian official last week, and circumspection-if not awe-is the natural mode of Oval Office visitors anyway. The main damage done would seem to have been to Mr. Nixon himself-both politically and operationally. The bugs, said a departed Nixonian, inevitably stifle high-level willingness to speculate and disagree on important policy matters. "Nobody," he said, "wants to come out of one of those decision-making things in the history books the way Adlai Stevenson got clobbered in the 1962 missile crisis."

|