The Nixon Tapes

(Newsweek, July 30, 1973)

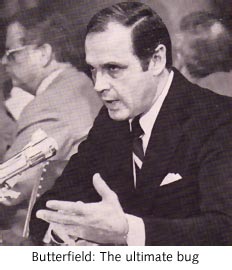

"Mr. Butterfield, are you aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the President?"

"I was aware of listening devices, yes sir…"

With that flat preamble, the cornucopia of disasters called Watergate spilled out yet another bit of stunning news last week-and threatened to make Richard Nixon's last line of defense untenable. The agent of his latest embarrassment was an obscure ex-staffer named Alexander Butterfield, who ruefully admitted before the Senate Watergate committee that Mr. Nixon-in the interests of history-had been secretly taping everything said in his offices and on his telephones for at least two years. The testimony on its face suggested that Mr. Nixon had been sitting on a whole trove of hard evidence of his guilt or innocence in the scandals, and it loosed very nearly irresistible pressures even among his surviving friends to surrender it. "If he doesn't," one White House higher-up said glumly, "I think he is dead."

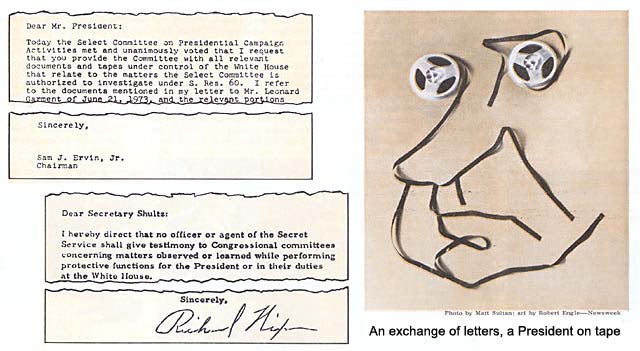

The President's first impulse was to fight-feeling, by some accounts, that the committee was trying "to get" him. Aides suggested that the tapes were privileged Presidential documents, and Mr. Nixon himself dispatched orders from Bethesda naval hospital that the Secret Service men who had wired the White House were not to testify about it. The President thereafter repaired to Camp David for yet another of his lonely seventh-crisis sojourns, this time to frame a letter to the committee answering its urgent request for the tapes. A few friends thought that he might find some way to yield without picking a constitutional fight; even committee chairman Sam Ervin was briefly tricked by a hoaxer into believing that Mr. Nixon had capitulated. But the word at the weekend was that the answer would be no-Mr. Nixon would unwire the White House but would not give up the tapes.

It was a choice calculated to please no one, a patently unsatisfactory answer to a painful and quite possibly deadly dilemma. The tapes, assuming their authenticity, could presumably settle once and for all the merit of John Dean's still unanswered accusations that the President was criminally involved in the Watergate cover-up. To withhold such critical evidence from the committee or from special prosecutor Archibald Cox would be to invite the suspicion that Mr. Nixon indeed has something to hide-and thus, said one House Democrat, to "convict himself." Yet to release the tapes could damage or even bring down his Presidency if they show he had any guilty knowledge of the conspiracy. "The details wouldn't even matter," worried one White House man. "The goddam balloon is on the ceiling right now, and I'm scared it's just about to go through."

'Plain Poppycock'

Mr. Nixon's survival as President was thus more critically on the line than ever when he came out of the hospital at the weekend after an eight-day bout of viral pneumonia. He had made a gallant show all week of running the government from his bed at Bethesda, shaking off first his 101-degree fever and chest pains and later the achy malaise they left behind; he met with aides, issued his phase-four-economic program and alternately unnerved and delighted his doctors with his refusal to act like an invalid. He emerged looking underfed but hale and returned to the White House, where scores of staffers had been turned out onto the South Lawn to welcome him. Mr. Nixon seized the moment for a pep talk denying any thought of quitting for reasons of health, humiliation or anything else. "That," he said, "is just plain poppycock…Let others wallow in Watergate-we are going to do our job."

But Mr. Nixon returned to a government in siege. The latest Gallup poll, taken after Dean's testimony and before the disclosure of the tapes, showed his popularity shriveled to 40 per cent-his lowest level yet. The first visible results of phase four were uniformly bad notices and gloomy predictions of a breakaway rise in food prices. The Administration was entangled in a painful new scandal-the discovery that it had papered over the secret bombing of Cambodia with falsified records. Prosecutor Cox found the corruption so multifarious that he had to ask for a second grand jury to handle the spillover. A second big company, Ashland Oil, confessed to an illegal GOP campaign gift of $100,000 from corporate coffers. And the Ervin committee was relishing the B-movie scenario of how the Nixonians dealt out more than $417,000 in hush money to the Watergate burglary gang; this week and next, the senators planned to call sometime White House topsiders John Ehrlichman and H.R. Haldeman-and thus inch the inquiry two steps closer to the top.

Sorest of all was the discovery, in the thick of the worst bugging scandal ever, that Mr. Nixon had bugged himself-had covertly taped conversations with everybody from Boy Scout troops to Leonid Brezhnev at least since the spring of 1971. The practice is technically legal if one party to the conversation consents,* and other Presidents have done it selectively. But Mr. Nixon's undiscriminating sweep had about it a 1983 ˝ aura that appalled some of the luminaries who had been taped.

The reaction abroad was diplomatically subdued, though Britain's Prime Minister Edward Heath was said to be disturbed, and one Japanese leader guessed that future talks with Mr. Nixon might have to be conducted walking through a park. The home-front reactions were less tactful. Robert Byrd, the Senate Democratic Whip, called the disclosure "one more shovelful on the dungheap." Philadelphia's super-cop Mayor Frank Rizzo, a Nixon backer in 1972, said wiring people was "un-American." And the AFL-CIO's George Meany found it "fantastic."

The far graver issue still was what the Nixon tapes may tell about the President's involvement in Watergate-and so about his life expectancy in the Presidency. No less sturdy a friend than John Ehrlichman agreed that the tapes are potentially "the ultimate evidence," and that they ought to come out. To resist now, moreover, would provoke a long, nasty test of will and prerogative with both the Ervin committee, which will try to subpoena them, and with Cox, who is pledged to raise hell publicly if the Administration withholds anything from him. But still the President held back; his silence invited speculation as to what was really in the tapes, and not even the kindest guesses buzzing around Washington last week were very flattering to him. Among the hypotheses:

The far graver issue still was what the Nixon tapes may tell about the President's involvement in Watergate-and so about his life expectancy in the Presidency. No less sturdy a friend than John Ehrlichman agreed that the tapes are potentially "the ultimate evidence," and that they ought to come out. To resist now, moreover, would provoke a long, nasty test of will and prerogative with both the Ervin committee, which will try to subpoena them, and with Cox, who is pledged to raise hell publicly if the Administration withholds anything from him. But still the President held back; his silence invited speculation as to what was really in the tapes, and not even the kindest guesses buzzing around Washington last week were very flattering to him. Among the hypotheses:

That the tapes tend to absolve Mr. Nixon and that he has delayed releasing them to sandbag the Ervin committee. This theory-current among the more hopeful Republicans-holds that the President, if not simon-pure, is at least too shrewd to have said anything damaging on tape; he has merely been waiting for the neat moment to clear himself, discredit the Ervin inquiry and set off a backlash of sympathy powerful enough to revivify his Presidency. But this version requires a belief in Mr. Nixon's masochism as well. "If he had the evidence," said one dubious senator, a ranking Republican, "why did he put the country through this incredible uncertainty that has hurt the government, damaged both parties, depressed the economy and made us the laughing stock of the world?"

That the tapes, if they surface at all, will be doctored to exonerate Mr. Nixon. Tapes can be made to do practically anything-a point committee counsel Sam Dash used to make to his law students by having a lecture of his taped and then doctored into a convincing confession to murder-but the technology is extremely tedious; one Army intelligence veteran guessed it would be almost impossible to make undetectable fakes of the dozens of conversations involved in the available time. Still, in the demi-paranoia(sic) of post-Watergate Washington, the suspicions persist. "Hell," said one influential House Democrat, "there's not a member up here who doesn't believe those tapes have been doctored-and if they haven't yet, they will be."

That the tapes are authentic-and are too damning to the President to see the light of day. This theory, by far the most prevalent, explains the president's resistance to yielding the tapes as a calculated risk-a gamble that he can live with suspicions more easily than with what the tapes might tell. John Dean, for one, was said by associates to have been "on cloud nine" since he first heard along with the rest of America that his conversations with Mr. Nixon were on tape; any one of them, he told a friend, "would destroy the President." The suspicion was surprisingly pervasive even among loyal Republicans. "I think what the President should do next," said one GOP senator, "is write a nice, warm letter to Spiro Agnew. He may need him for executive clemency."

'I Hoped You Wouldn't Ask'

That Mr. Nixon's closely held secret got out at all was another of the accidents that have characterized the history of Watergate. Butterfield, who had departed the White House in March to head the Federal Aviation Agency, wasn't even on the Ervin committee's working list of witnesses; he was added only a fortnight ago when one of his old White House colleagues, Gordon Strachan, mentioned him in passing during an interview with the committee staff. He was called in for questions, and one of the committee's Republican minority lawyers, Donald Sanders, asked him a just-fishing question about whether there was anything to Dean's suspicions that one of his last talks with the President might have been taped. "I really hoped you guys wouldn't ask that," Butterfield answered, looking pained-whereupon he spilled out the whole tale of the wired White House.

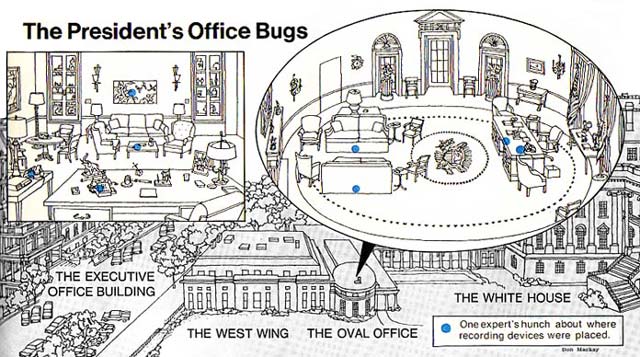

The committee, scenting blood, worked Butterfield instantly into its schedule-and kept the secret until he himself reluctantly sprung it on America. Mr. Nixon, as Butterfield told it, had passed down the order to start running tapes "to record things for posterity-for the Nixon library. The President was very conscious of that kind of thing." With Butterfield as liaison, the Secret Service installed supersensitive bugs in both the Oval Office and in the President's hideaway in the Executive Office Building; the devices were switched on when Mr. Nixon came into the room and started recording when anyone began talking, even in the lowest tones. A button-operated recording system went into the Cabinet Room but didn't work very well. And four phones were wired to record whenever Mr. Nixon picked up the receiver-one in the Oval Office, another in the EOB, a third in the Lincoln Sitting Room at the White House and a fourth in the President's lodge at Camp David. Mr. Nixon himself couldn't turn off his office bugs without asking, Butterfield said, and he never asked; he seemed in fact to be "totally, really, oblivious" that he was constantly on candid microphone.

Butterfield had assumed that his superiors had already informed the committee of all this and was visibly unhappy at breaking the news; he told his mother by long-distance phone that night that he was likely to be "a hero to some people and a dirty dog to others." The import of his testimony was instantly apparent. The tapes, cached by Butterfield's account in closets somewhere in the EOB, presumably included Mr. Nixon's conversations not only with Dean but with a whole run of his fellow principals in the case-Ehrlichman, John Mitchell, Charles W. Colson and Butterfield's old boss, Haldeman. "What would be the best way to reconstruct these conversations, Mr. Butterfield?" Sam Dash asked innocently. "Well," said Butterfield dismally, "in the obvious manner…obtain the tape and play it."

Point Counterpoint

The committee moved swiftly to do precisely that-and the White House acted with equal speed to block the move. The White House Watergate lawyer-in-residence, J. Fred Buzhardt, rushed out a stopgap letter confirming that the sound system existed, that it was still running and that, after all, Lyndon Johnson had had one like it. But that was as much as the Nixonians were willing to give. When Ervin and his vice chairman, Howard Baker, sat down to question one of the Secret Service men who had planted the bugs, a Treasury Department lawyer interrupted them with a letter from the President himself directing that no agents testify about anything they had "observed or learned" on White House duty-the tapes transparently included.

The ground was the constitutionally uncertain doctrine of Executive privilege. Mr. Nixon, who first claimed and later renounced the principle, has lately resurrected it; Ehrlichman is expected to raise it this week as a shield against some questions, and Mr. Nixon himself has invoked it to keep from having to testify himself or to surrender his papers-or tapes-to the committee. His argument is tenuous. Past Presidents have released papers and even occasionally testified before Congress; Mr. Nixon seems by contrast to be contending that to give up the tapes-even though they would prove his innocence-would set a damaging precedent and so weaken his high office.

In any case, there is neither precedent nor constitutional theory to suggest that Executive privilege would permit a President to suppress evidence in a criminal case, and Dash for one argued snappishly that it was "late in the day" for anyone to try locking up the tapes. But the committee decided against a confrontation that could tie up its inquiry for months of litigation. Ervin sent the President a letter asking for "all relevant documents and tapes" as quickly as possible. "My hopes are great," he said. "My expectations are small."

His hopes as against his expectations seemed momentarily to be answered two days later when, while Ervin was off running the hearings, a caller purporting to be Treasury Secretary George Shultz telephoned his office and asked urgently to speak to him. The call was put through to a booth in the Senate Caucus Room; Ervin took it there-and to his pleased surprise got "Shultz's" promise that the tapes would be made available. Ervin told Baker, and the two of them, all smiles, announced what seemed a famous victory.

It lasted barely five minutes. The bubble burst when White House communications director Ronald Ziegler's secretary came bursting into his office stammering, "Mr. Ziegler! Ervin says we're giving up the tapes!" Ziegler dashed down the gold-carpeted corridor and found chief of staff Alexander Haig already on the phone to Shultz, who flatly denied having called Ervin at all. The President himself phoned from the hospital while his senior people were still in Haig's office; his reaction was officially described as "quite unusual"-and manifestly opposed to springing the tapes.

'A Trusting Soul'

This news was relayed to Ervin, who made one last chagrined check with Shultz, then confessed that he had been taken. It was, he said, "an awful thing for a very trusting soul like me"; he couldn't resist adding that he had bitten because what the false Shultz had promised "was a rational thing that should be done."

The signals that the White House had decided otherwise are likely to force the committee into just the sort of confrontation it doesn't want. Its staff was already at work last week pulling precise meetings and dates out of the welter of testimony in hand. The list will surely include Dean's own conversations with the President, beginning last September (when he says Mr. Nixon congratulated him for having "contained" the investigation) and accelerating through February and March (when, according to Dean, they discussed the tactics of the cover-up and the likely complicity of several senior Nixonians). The committee will also want tapes of John Mitchell's supposed speak-no-evil talks with Mr. Nixon, and of the conversations in which Dean alleges that Ehrlichman and Colson sought Executive clemency for one of the convicted Waterbuggers. The probable strategy will be to subpoena 35 or 40 tapes-a list long enough to deter any effort at doctoring, and specific enough to head off a charge that the committee is merely fishing.

Cox, too, will be pressing for a set of tapes, and his demand could be more perilous for Mr. Nixon even than an Ervin committee subpoena. His special prosecution force, for one thing, is part of the executive branch of government; the President cannot persuasively argue that Executive privilege or the separation of powers between branches gives him the right to withhold pertinent papers and tapes from Cox. Neither can he lightly refuse to yield evidence as important as the tapes to the courts. If Mr. Nixon tries even so to stonewall the prosecutors, he risks the certainty that Cox will squawk out loud-and the even more devastating possibility that he might resign in protest.

The dominant mood at the White House was nevertheless to resist the inexorably rising pressures. Not everybody in Mr. Nixon's diminished circle of advisers was persuaded he should fight; the Senate GOP leadership urged him to pick some retired senator of high integrity-John Williams of Delaware, for example, or John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky-to review the tapes and report his findings to the committee. A group within the White House itself, led by senior staffer Melvin Laird, advocated some kind of accommodation-at least releasing selected written transcripts or digest of the tapes. But the senators were unlikely to accept anything short of the tapes themselves, and the White House in its present garrison frame of mind was undisposed to give them anything at all. "A lot of us," said one staff hawk, "think the President ought to tell the committee to go f---- itself"-and in the end the White House hawks apparently prevailed.

The President in any case came back to the White House in full fighting spirit. His pep talk on the lawn was full of high resolve neither to go slow as his doctors had advised ("No one in this great office…can slow down") nor to quit. He had been "rather amused," he said, by speculation that his current troubles had brought on his illness and that he might not be fit to carry on. "We are going to stay on this job until we get the job done," he said to thunderclaps of applause. "…What we were elected to do, we are going to do."

Yet for all his show of tenacity under fire, his government was in fact wallowing in Watergate-and now the discovery of the Nixon tapes has brought him to his most dangerous passage yet. He evidently planned to try suppressing the tapes; he may even succeed. But resistance can only deepen the suspicions that have eroded Mr. Nixon's capacity to govern and damaged his standing in history. "The people want to hear the tapes," said one Ervin committee source-and to deny them now would invite the guess that what the ultimate bug picked up incriminates the President.

* Mr. Nixon was in apparent violation of telephone-company regulations requiring a warning beeper at fifteen-second intervals when a call is being recorded. The phone company, nudged by the Federal Communications Commission, dutifully advised the White House of this dereliction in a formal letter last week - but acknowledged that it is unlikely to invoke the only penalty: removing the President's telephone.

|